Ong Kian Peng Julian v Singapore Medical Council and other matters

Can a Doctor’s Private WhatsApp exchanges bring Disrepute to the Medical Profession?

Ong Kian Peng Julian v Singapore Medical Council and other matters [2022] SGHC 302

I. Executive Summary

Doctors are medical professionals in whom patients trust and confide their information. It is also expected that this information will be treated with dignity and respect, and will be used for proper purposes. But what happens when the line between a doctor’s personal and professional life is obscured? Specifically, what if doctors shared their patients’ contacts with each other in private WhatsApp exchanges? Would that warrant punishments like a term of suspension?

The High Court (“HC”) considered whether a WhatsApp exchange between two doctors, where one had shared a patient’s contact with the other, could amount to improper conduct that brought disrepute to the medical profession. It held that such actions could amount to improper conduct that warranted significant penalties. It further provided guidelines on how to use the sentencing framework set out in Wong Meng Hang v Singapore Medical Council [2019] 3 SLR 526 (“Wong Meng Hang”), the leading case on penalties for medical professional misconduct, in such cases. The HC also considered whether the “similar fact evidence” rule applied to disciplinary tribunal proceedings.

II. Material facts

Two doctors, Dr

Ong Kian Peng Julian (“Dr Ong”) and Dr Chan Herng Nieng (“Dr Chan”),

were found guilty by a Disciplinary Tribunal (the “DT”) of improper

conduct which brought disrepute to the medical profession under section 53(1)(c)

of the Medical Registration Act (Cap 174, 2014 Rev Ed) (the “MRA”). This

was based on an exchange of messages they had in March 2018 (the “Messages”),

where Dr Ong had forwarded the contact information of a patient (“K”) to

Dr Chan.

K was a property agent who had consulted Dr Ong on 19 March 2018, following which Dr Ong obtained K’s consent to share her contact details with Dr Chan on the supposed basis that Dr Chan was looking to purchase a property. Shortly after, a WhatsApp conversation ensued between the two doctors, in the course of which K’s contact was forwarded by Dr Ong to Dr Chan. The messages are transcribed and numbered as follows:

| Message No. | Sender/Recipient | Message |

| 1 | Dr Chan to Dr Ong | U r just too stretched .. |

| 2 | Dr Chan to Dr Ong | Can ask her for drinks instead ? |

| 3 | Dr Ong to Dr Chan | [sends the contact details for K] |

| 4 | Dr Ong to Dr Chan | Feel free to play your game |

| 5 | Dr Ong to Dr Chan | Sure [replying to “Can ask her for drinks instead ?”] |

| 6 | Dr Chan to Dr Ong | Me? Out of the blue ask her? |

| 7 | Dr Ong to Dr Chan | I can recommend dilatation of her anus after her wounds heal |

| 8 | Dr Ong to Dr Chan | She’s expecting you re the property mah [replying to “Me? Out of the blue ask her?”] |

| 9 | Dr Chan to Dr Ong | I can’t decide to go thru the property route |

On 20 March 2018, Dr Chan started a conversation with K, discussing the possibility of purchasing an investment property (the “Follow-on Conversation”). However, they did not stay in contact and did not meet each other.

These WhatsApp exchanges were discovered later in 2018 when a complaint was filed against the two doctors for another matter, during which images of the exchange regarding K were uncovered. The Singapore Medical Council (the “SMC”) then initiated disciplinary proceedings against Dr Ong and Dr Chan in respect of the Messages, with the rest of the WhatsApp message exchanges between Dr Ong and Dr Chan (the “Remaining Messages”) appended to the SMC’s Complaint. The Remaining Messages were not the subject of any charges and did not concern K, but they documented conversations between the two doctors that discussed various other sexual encounters they each had.

Dr Ong and Dr Chan each faced a charge of improper conduct that brought disrepute to the medical profession under section 53(1)(c) of the MRA. Dr Ong was found guilty on the grounds that he had failed to treat his patient K with due courtesy, consideration and respect. This was a breach of Guideline C1 of the SMC Ethical Code and Ethical Guidelines (2016 Edition), which requires doctors to display a high standard of professional conduct in their dealings and interactions with patients”. (1) The DT imposed an eight-month suspension term.

Dr Chan was also found guilty due to his collusion with Dr Ong, despite the DT finding that Guideline C1 did not apply to him because K was not his patient. The DT found that an “irresistible inference” could be drawn from Dr Ong’s and Dr Chan’s conduct, the Messages, and the Follow-on Conversation that both doctors had colluded to introduce K to Dr Chan, with Dr Chan pretending to be a genuine property purchaser, when the real intention was for Dr Chan to get to know K socially and attempt to engage in sexual activity with her (the “alleged collusion”). As such, the DT imposed a five-month suspension term.

The DT imposed both sentences based on the factors and sentencing framework set out in Wong Meng Hang v Singapore Medical Council [2019] 3 SLR 526 (“Wong Meng Hang”). The doctors appealed against their convictions and sentences. SMC also appealed against the sentences meted out by the DT, on the basis that they were manifestly inadequate.

III. Issues

On appeal, both doctors raised broadly similar arguments. First, they claimed it could not be inferred from the Messages that they had been in collusion. Second, they claimed that the Remaining Messages should not have been considered by the DT because they consisted of inadmissible “similar fact evidence”. Viewed in isolation, without reference to the Remaining Messages, there was insufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that both doctors had colluded as alleged.

The HC thus considered the following issues:

(a) whether the Messages alone were sufficient to show the alleged collusion,

(b) whether the alleged collusion brought disrepute to the medical profession under section 53(1)(c) of the MRA,

(c) whether the Remaining Messages that did not concern K were admissible, and

(d) the appropriate sentence to be imposed.

The HC agreed with the DT’s findings and dismissed both doctor’s appeals. The HC also increased the doctors’ sentences: from eight months to two years for Dr Ong, and from five months to 18 months for Dr Chan.

A. Whether the Messages alone were sufficient to show the alleged collusion

The first issue was whether the Messages, when read on their own, was capable of showing that Dr Ong’s sharing of K’s particulars with Dr Chan was to enable the latter to engage in sexual activity with her. The HC found that that Message Nos. 2, 5 and 6 clearly showed that Dr Chan was entertaining the idea of asking a woman out for drinks upon Dr Ong’s suggestion. Considering this in light of the fact that Dr Ong had forwarded K’s contact information in Message No. 3 and the references to the “property” and “property routes” in Message Nos. 8 and 9, the HC held that it was “simply impossible” to arrive at any other conclusion other than Dr Chan was entertaining the idea of asking K out for drinks and that Message No. 2 was a reference to K, since K was a property agent.

Messages Nos. 8 and 9 also led to the “logical and inexorable conclusion from the plain text of the Messages” that the doctors were discussing how Dr Chan was to approach to invite her for drinks, with the potential purchase of property being the possible way for Dr Chan to initiate the invitation.

The HC pointed out that it was difficult to understand why Dr Chan seemed hesitant and apprehensive about how to contact K if the conversation was genuinely about a possible property purchase. His hesitancy over the method in which he was to secure a physical meeting with her and the use of “property” as a “route” made it difficult to accept that the actual subject matter of the Messages was about property. Message No. 7 would also “completely erase” any doubts about what the doctors were discussing about. There was “simply no reasonable way a conversation about the innocuous introduction of a property agent could cohere with what was said in that message”. When seen in the light of the entirety of the exchange, it became “inescapable” that the subject-matter of the Messages was not about property but about a potential sexual venture.

The HC also

stressed that the “heart of the charges” was the misuse of a patient’s contact

information by Dr Ong, with the participation of Dr Chan. It was not necessary

for Dr Chan to have met K or to have engaged in any sort of sexual activity

with K for the charges to be made out. The point of the exercise of contacting

K about a property was to conceal the real intent behind a façade of normalcy.

Thus, the HC

was satisfied and agreed with the DT that Dr Ong had set up an introduction for

K to be contacted by Dr Chan under the pretext of the latter’s feigned interest

in a potential property transaction, when both he and Dr Chan knew that this

was not the real point of the introduction. Rather, it was to enable Chan to

pursue his own agenda, which they both knew was for him to try and have sex

with K.

B. Whether the alleged collusion brought disrepute to the medical profession under section 53(1)(c) of the MRA

A key element

for the charge to be made out (under section 53(1)(c) of the MRA) was

whether public confidence in the medical profession would be damaged by the conduct

of Dr Ong and Dr Chan. The HC approached this inquiry by considering whether a

reasonable person, on hearing about what Dr Ong and Dr Chan had done, would

have said without hesitation that they should not have done it.

The HC

reiterated that the relationship between the doctor and his patient exists for

the benefit and best interests of the patient. The complexion of that

relationship carries with it a very real potential for exploitation, which was

precisely what Dr Ong had done for the potential benefit of Dr Chan. Dr Ong had

obtained K’s consent to disclose her contact details to Dr Chan under false pretences

by misrepresenting to K that a friend of his would contact her for a legitimate

business purpose, when he was actually passing his patient’s contact in

betrayal of her trust, with the knowledge that that Dr Chan would try to

convert that introduction into an opportunity to satisfy his own “lustful

appetite”. Dr Ong “certainly did not treat K with respect and dignity”.

Dr Ong’s

conduct was thus “incompatible” with Guideline C1, which requires doctors to

treat their patients with “courtesy, consideration… and respect… without

exploitation”. The HC also agreed with the DT that ethical rules and guidelines

have to be interpreted and read in a manner which gives effect to their

underlying spirit and intent. It was beyond a reasonable doubt that Dr Ong’s

conduct was something a reasonable person would conclude that he ought not to

have done.

For Dr Chan, the

HC held that he knew the ethical rules that applied to him, and knew that K was

Dr Ong’s patient and that Dr Ong was passing K’s contact information to him. Although

Guideline C1 did not apply to Dr Chan since there was no doctor-patient

relationship between him and K, he had nonetheless fully acquiesced and

participated in a scheme where a fellow doctor was acting in violation of

Guideline C1. A member of an honourable profession who receives information

from another member of the profession which he knows was handed to him in

breach of that other member’s duty could not say that he played no part in that

breach where he intended to act on that information. Thus, Dr Chan’s conduct in

receiving confidential patient information from another doctor in these

circumstances and for these purposes, was conduct that a reasonable person

would conclude he should not have engaged in.

C. Whether the Remaining Messages that did not concern K were admissible

Both doctors

relied on the case of Law Society of Singapore v Constance Margreat Paglar

[2021] 4 SLR 382 (“LSS”) for the proposition that “similar fact

evidence” was generally inadmissible in disciplinary proceedings due to its

quasi-criminal nature, and thus the Remaining Messages ought not to be

admitted. “Similar fact evidence” refers to evidence of past behaviour that may

show a disposition towards crime. The rationale for the rule excluding “similar

fact evidence” is to avoid the risk of convicting an accused based not on the

evidence relating to the facts at hand, but because of his past behaviour or

disposition towards crime.

However, the HC

held that LSS was simply restating the general position that “similar

fact evidence” was generally inadmissible, and was not inconsistent with

the leading Court of Appeal case of Tan Meng Jee v Public Prosecutor [1996]

2 SLR(R) 178 (“Tan Meng Jee”). Thus, similar fact evidence, while

generally inadmissible, can still be admitted if its probative weight

outweighed its prejudicial value. This is commonly determined with reference to

the cogency, strength of inference, and relevance of the evidence in question.

The HC did not

think that the issue of similar fact evidence was even relevant as the DT had

not considered the Remaining Messages as evidence pointing to propensity, but

rather as evidence that demonstrated and shed light on the true context of the

relationship between Dr Ong and Dr Chan, as well as their state of mind and

intention when discussing K. The HC noted that, given its conclusion that it

was not necessary to rely on the Remaining Messages to make out the alleged

collusion (as explained in section A above), the Remaining

Messages did nothing more than to confirm the conclusion arrived at based only

on the text of the Messages.

Regardless, the

HC held that the Tan Meng Jee test would be fulfilled in the present

case. The Remaining Messages were relevant and admissible for the limited

purpose of demonstrating the nature of the relationship and dealings

between the doctors, which in turn was useful in shedding light on the meaning

of the Messages. Having considered the three factors of cogency, the

strength of inference, and relevance, the HC was satisfied that the probative

weight of the Remaining Messages outweighed their prejudicial effect. Neither

doctor had disputed the authenticity of the Remaining Messages or disputed that

they showed the doctors’ history of introducing women to each other with a view

to trying to engage in sexual activity and to discuss their sexual exploits and

appetites. In this light, the Remaining Messages are not only relevant but also

significant in contextualising what Dr Ong and Dr Chan were discussing in the

Messages, as well as demonstrating what they knew about each other, and their

respective sexual exploits and appetites.

The HC

concluded that the Remaining Messages were not pivotal to its analysis of the

proper inference to be drawn from the Messages. There was sufficient evidence

without considering the Remaining Messages to show the real point of the

WhatsApp exchange. But the Remaining Messages did help fortify the

conclusion that the doctors were not discussing a property transaction in

relation to K in the Messages.

D. The appropriate sentence to be imposed

The HC first noted that the four-step sentencing framework as stated in Wong Meng Hang (the “Wong Meng Hang framework”) had been set out in relation to cases where harm to a patient was caused by deficiencies in a doctor’s clinical care, and would not be applicable to other types of misconduct which lie within or outside a doctor’s professional responsibilities, even though the same considerations of harm and culpability might be relevant. However, the parties did not dispute the applicability of the sentencing framework here. Further, the SMC had extended the applicability of the Wong Meng Hang framework to both clinical and non-clinical offences through its Sentencing Guidelines for Singapore Medical Disciplinary Tribunals, so as to guide the DT in sentencing. Regardless, the HC stressed that it was important to bear in mind the nuances of each case when deciding sentencing.

The Wong Meng Hang four-step framework is as follows:

(i) Step 1: Evaluate the seriousness of the offence with reference to harm and the culpability of the doctor.

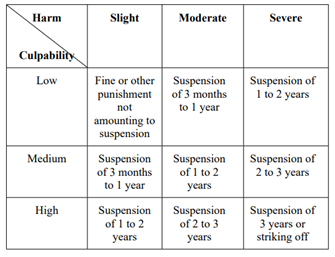

(ii) Step 2: Identify the applicable indicative sentencing range using the following sentencing matrix:

(iii) Step 3: Identify the appropriate starting point within the indicative sentencing range.

(iv) Step 4: Adjust the starting point by taking into account offender-specific aggravating and mitigating factors.

As applied to Dr Ong

The HC found that the case involved significant harm to public confidence in the medical profession. What Dr Ong did was an abuse of the trust and confidence that a patient had reposed in him, for the potential sexual benefit of Dr Chan. Further, it was not only disrespectful to K, but it also dehumanised her into an object for sexual gratification.

That no actual harm was caused to K by either Dr Ong or Dr Chan missed the point. Such an assertion was true only in the limited sense that she was not compelled to engage in sexual relations with Dr Chan under false pretences. But it could not be denied that she suffered humiliation and indignity as a result of what Dr Ong and Dr Chan did to her, and the fact that she was Dr Ong’s patient made it all the more aggravating. If actual physical harm had been caused to K, the sanction called for would likely have been a striking out order.

The HC reiterated that the harm to public confidence could not be understated. Patients are entitled to expect that their doctors will display a high standard of professional conduct in their dealings and interactions with them. This extends to how their doctors handle their personal information and their details even after the end of their interactions. The amount of harm was thus on the higher end of the moderate range.

Dr Ong’s culpability was also on the high end of the medium range First, he obtained K’s supposed consent under false pretences. Second, he was the one who had initiated the act of collusion with Dr Chan, by forwarding K’s contact details to Dr Chan. Third, his actions were callous and an intentional departure from the conduct reasonably expected of a medical practitioner. There was “simply no possible justification” for dealing with a patient’s information in the way Dr Ong dealt with K’s information.

Under the sentencing matrix, the starting point was a suspension between one to two years. Dr Ong’s unblemished record as a medical practitioner did not have any mitigating weight as it was not a case that involved his clinical judgment or professional expertise. Conversely, the fact that he was a senior doctor of more than 20 years’ standing amplified the negative impact his misconduct would have had on public confidence in the medical profession.

As a key sentencing objective in the present case was one of general deterrence, it was imperative that a clear message be sent to the medical profession that such conduct is utterly unacceptable, and that harsh consequences would befall those who might be considering similar acts. Dr Ong also did not express genuine remorse as he maintained that he had not committed any professional misconduct. The principle of general deterrence and the need to protect public confidence and uphold the standing of the medical profession justified a longer length of suspension of two years (as compared to the eight months imposed by the DT).

As applied to Dr Chan

Dr Chan’s case involved a few material differences compared to Dr Ong. Firstly, he was the recipient of the contact information of K and played a more “passive” role. Additionally, K was not Dr Chan’s patient, so there was no doctor-patient relationship with K. Nonetheless, the HC held that Dr Chan’s role could not be understated. He had colluded with Dr Ong despite knowing that K was Dr Ong’s patient. After receiving K’s contact information, he had proceeded to contact K, although he did not eventually follow through by meeting K or attempted to engage in sexual relations with her.

Similar to Dr Ong, the HC considered harm that was caused to the public confidence in the medical profession to be significant. There could be “no doubt” that the public would regard with consternation the fact that one doctor had abetted another doctor’s abuse of the trust of a patient for his potential personal benefit. There was thus no reason to find that the harm occasioned by Dr Chan should be lower than that occasioned by Dr Ong.

For his culpability, the HC accepted that Dr Chan had not actively sought K’s contact information, though he did then use it to contact her. However, Dr Chan admitted that he knew that K was Dr Ong’s patient at the time the Messages were exchanged. Following from the HC’s holding of the proper interpretation of the Messages and inferences to be drawn from them, it would have been obvious to Dr Chan that Dr Ong would not have had the consent of K to share her contact information with Dr Chan for the purpose of his potential sexual gratification. In the circumstances, his culpability was assessed as “medium”. As such, the HC found that the DT’s sentence of five months’ suspension was manifestly inadequate and that the term of suspension should be significantly longer, i.e. 18 months (as compared to the five months imposed by the DT).

IV. Lessons Learnt

As part of an honourable profession, one ought to uphold oneself to the high standards of trust and confidence required of them, even in their own private lives. The HC also clarified that “similar fact evidence” is admissible in DT cases if the probative value in admitting such evidence outweighs the prejudicial effect of doing so, and can be used to provide context and fortify conclusions drawn from other pieces of evidence. Overall, harm not only to a victim, but also to public confidence in such professions will be an important factor in determining whether disrepute is brought to the profession as a whole.

Written by: Lai Zu En, 3rd-Year LLB student, Singapore Management University Yong Pung How School of Law.

Edited by: Ong Ee Ing (Senior Lecturer), Singapore Management University Yong Pung How School of Law.

Footnote

(1) A breach of any ECEG guidelines can result in doctors being charged under section 53(1)(c) of the MRA.